As much of a pleasure as it was to appear at the Shanghai International Literary Festival with Jen Bervin, Jen Hyde and Wen Jin, it was one mixed — as is always the case for me here in Shanghai — with significant measures of the odd and the off.

Don’t get me wrong: One of the things I like about life in Shanghai is that the “odd and the off” are clearer in the mix than might otherwise be (or at least this is how it seemed to me prior to the Trumpening, one effect of which has been that many dissonant tones and out-of-sync beats that the producers of the Washington Consensus mix of the late-2oth century hit “Pax Americana” had studio-polished to the point of inaudibility for the ears of smooth-sounds-loving progressives are now gratingly, harshly present in the cacophonous “Make America Great Again” alt right-produced nü metal-new country-no soul-“Trumpism is the new punk rock” undercut hate hit dominating the charts of late).

One place, of course, to detect the odd and the off, is within various neighborhoods of the regime of censorship — the softer the censorship, the better. The hard stuff tells you what you already know. The soft stuff can remind you of what you’d already forgotten — including the fact that yes, discretion is often the better part of valor.

Among the Anglophone expat community in Shanghai, the softest form of censorship is certainly that of the self- variety. The current example, which I go into below: I submitted copy on our Poetry Panel to the SILF, and it was not just altered editorially but critically, and with the Public Security Bureau in mind.

The SILF organizers are fantastic people. They work hard to make an amazing series of events possible, events at which almost anything and nearly everything are discussed with candor, openness and degrees of freedom that would likely shock the many Americans whose ideas about China often seem frozen in some fuzzy Cold War-Cultural Revolution matrix.

At present you can talk about Tiananmen and Tibet, Mao’s vast bad side (all bad? Discuss…) and Xi’s dye-job freely and openly — within expat-saturated Anglophone zones and bubbles (SILF being one, my employer certainly another, the Shanghai Foreign Correspondents Club yet another, and so on).

But you can’t — or you feel you shouldn’t — be too open about it, and you must be ready to defer to the actual censor (if you publish anything for distribution within the PRC) or the censor in your head (if you have, as you do, relationships with PRC citizens, in particular Party members or those who the Party is or may be watching with particular intent).

And state surveillance and censorship dovetails in interesting ways with what other expats want to hear. They’re generally — we are generally — business people. That’s what’s tolerated, more or less: Come for business, do your business, and don’t interfere with anything that’s not your business, such as the policies and practices of the PRC, both internal and external. Have your events and talks and talk about what you like (a good model for keeping an eye on the outsiders, for sure, letting us tend our little gardens of 100 blooming flowers) but keep it to yourselves and watch your words if they might leave the Special Zone (I work in a very special zone).

This all worked in a couple of ways when it came to the poetry events I organized and participated in at SILF. In the grand scheme, exceedingly minor, yet, even as minor symptoms, quite telling with respect to the grand scheme.

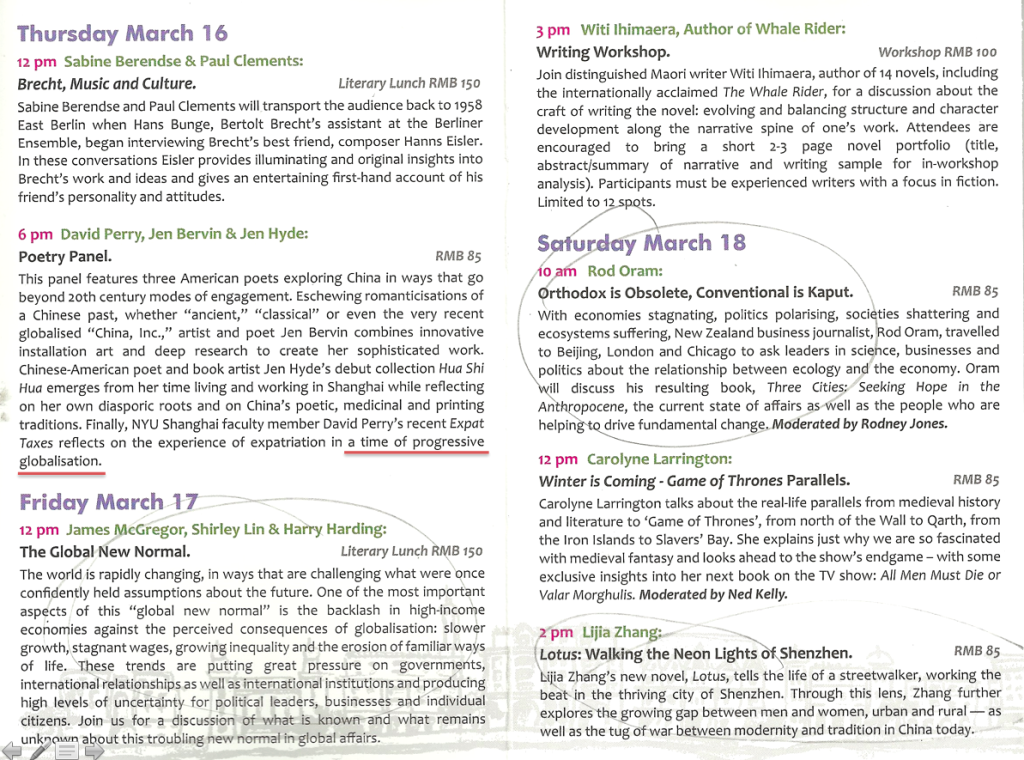

The first: My submitted promotional copy for our event went from describing my work as reflecting on “the experience of expatriation in a time of growing planetary crisis, even as China and its expat population are celebrated (and often celebrate themselves) as engines of progressive globalization” to reflecting on “the experience of of expatriation in a period of progressive globalisation.”

The organizers are careful readers and good editors, so I didn’t think, when I saw the printed brochure (see the scanned image below) that this was just an editing error. My suspicion was confirmed when I pointed out that the brochure copy was a long way from my intended meaning, in fact, it was nearly opposite. The email response: “…we were simply trying to avoid any controversy on the printed program since the PSB does check up on us.”

Printed matter is a real sticky point to be sure, and I understood. Digital content is different, and the organizers changed the Web copy to “the experience of expatriation in a time of globalisation in deepening crisis.”

Good enough, and I’m glad to have the print brochure souvenir, even as it grates. It’s the the off and the odd, after all, and I like it like I like a look of agony (or at least awkwardness or embarrassment), because I know it’s (more likely to be) true: yes, we are and I am party to censorship, and we do it ourselves.

The other point of soft censorship has more to do with poetry and what “big readers” of the sort who organize and participate in and attend things like expatriate literary festivals imagine it does and what its for. What does it do? Feminine feels, I think, based on the responses I get from most of my fellow expats. And maybe occasionally expressions of masculine scampishness (wine, women, song)? Along with, of course, mainline hits of curio-grade Orientalism (rice wine, Chinese women, Song Dynasty artifacts).

SILF is great at what the Shanghai Foreign Correspondents Club is great at: giving journalists (often financial and business journalists) a platform to do what they do in their writing: report on China, China and the West, China’s rise, China’s economy, cultural trends in China, and so on — an aspect of the whole that culminates in the Financial Times debates, with this year’s question being “Has Western Democracy Been Discredited?” (I missed it, but I believe they came down on the “no” side in the end.) It’s also good at bringing in China-related fiction writers (this year’s star: Amy Tan) and, occasionally, actual Chinese writers who have been translated or write in English.

Along the way it does a lot of other good things, having created space for a diverse range of engaged writers and readers, as the little bit of the program shown in the scanned bit of the brochure below hints at: “Brecht, Music and Culture” (missed that one, I’m truly sad to say); recovering business journalist Rod Oram on, ultimately, the dreadfully difficult and dark subject of “seeking hope in the Anthropocene” (the spot-moderator, Rodney Jones, blithely admitted that he didn’t know what the Anthropocene was before he read Oram, and most of the audience didn’t quite seem to get it, which doesn’t inspire much hope, but talking about it at all is better than nothing); and Lijia Zhang’s new novel is about sex work in Shenzhen (I missed the event but talked to her later, and she might come to NYU Shanghai next year to give a reading).

But it’s not so good with poetry. I say this with enormous gratitude for having been giving the opportunity to organize this event, and I’d hope to do another (perhaps one on the very question of being “not so good with poetry”). I’m not surprised or offended, but it’s worth noting. It’s symptomatic.

Case in point: To fill a cancellation, I pulled together a reading with Nina Powles and Austin Woerner, in which I also read and previewed the Bervin and Hyde panel. The preceding event: “Duncan Clark: Pragmatism vs. Populism,” a talk on Clark’s Alibaba: The House that Jack Ma Built. It was packed, and justly so. Clark’s a strong speaker. He fulminated against Trump, he praised Ma, he hit the right notes for an audience full of globalist cosmopolitans (innovation and free trade good; populist nationalist politics bad). He joked, along the way, with an audience member who apparently shares the same yoga instructor as Jack Ma, and he closed by noting that “poetry” was up next, quipping that it would be time for “Berkeley and yoga.”

The poetry session was well attended, for a poetry session, but few of the attendees from the Clark session returned, which was too bad: Austin Woerner’s reading and talk on Ouyang Jianghe’s phenomenal Phoenix provided, arguably, far more insight into the workings and effects of global capital in the early 21st century than the business journalist’s pean to Jack Ma. Powles was strong, too, and a long way from yoga and Berkeley, but there we were, consigned by a quick quip to granola, fuzzy idealistic hippy-grade politics (I doubt he intended black bloc-driven no-platforming and window-smashing), and self-indulgent lifestyle consumerdom.

I might prefer the soft censorship of the PRC state, and our expatriate complicity therewith, to that arising from the deep cultural prejudice of that portion of the business journo class (and their knowing “China-hand” readership) wedded to fantasies of “progressive globalisation” and willfully ignorant of the degree to which “progressive globalisation” is, quite arguably, the very source of the Anthropocene.

You should read Rod Oram’s book, by the way; he’s a recovering business journalist who sees much of what the poet Ouyang Jianghe sees, and writes about it in Three Cities: Seeking Hope in the Anthropocene.