Reposting this old Poetry Project Newsletter review of Peter Culley’s Hammertown. One of my favorite poets, he’s also a favorite reviewer — his review of Clark Coolidge’s Far Out West, for example, has always really done it for me, packing more references into less space than almost anything else, ever (to say nothing of the ongoing catablogging of Culley’s favorite stuff over at Mosses).

Reposting this old Poetry Project Newsletter review of Peter Culley’s Hammertown. One of my favorite poets, he’s also a favorite reviewer — his review of Clark Coolidge’s Far Out West, for example, has always really done it for me, packing more references into less space than almost anything else, ever (to say nothing of the ongoing catablogging of Culley’s favorite stuff over at Mosses).

*

“His playing is beyond what I could say about it.”

—John Coltrane on Paul “Mr. P.C.” Chambers

“Probably intended for dance tunes or with dance tunes in mind.”

—Louis Zukofsky on John Skelton’s “To Mistress Margaret Hussey”

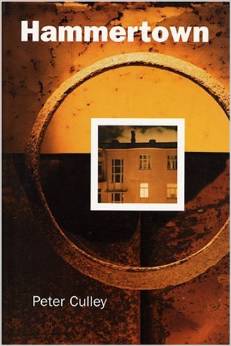

Presented in three sections of six poems each, Peter Culley’s Hammertown is experimental at its core — check the particle-accelerator serial mash of “Snake Eyes” — and, strangely, beautifully, classical on either wing of the triptych (or gatefold LP cover), as the poet deftly mixes modes and methods — a sustained lyricism shot through with riffs epistolary, pastoral, elegiac; leavened with sincere homage; ventilated by epic-ironic gestures. And then there are complete surprises, such as the doses of “tumbling verse” à la Skelton; Culley’s rhymes and snapped lines, written “with dance tunes in mind,” help leash the poems enough to keep their wilder energies from spinning the work off into space while nudging what can be a very dark book towards the light. There is nothing emptily virtuosic in Culley’s polyverse; on the contrary, I repeatedly felt the thrill of the new while plunging into “a mix without edge or limit” and, just as often and importantly, the satisfaction of frequent enough snatches of “an air familiar” to keep from losing too many wits to bear witness.

D.J. comparisons are as inevitable in describing Culley’s work as comparisons to bop are with, say, Kerouac. References — samples, quotes, splices, dubs — come quick and thick: to poets, musicians and artists by the dozens and to history, both global and local, with the local centered on the poet’s Vancouver Island home of Nanaimo. A product of Culley’s numerous enthusiasms (see also his bricoleur’s blog extraordinaire, Mosses from an Old Manse), Hammertown’s rich intertextuality never unbalances the work with clumsily dropped names or awkward stabs at the merely clever; rather, it lends Hammertown a sense of the “blithe complexity” that Culley finds in, say, the Afro-beat of Fela Kuti as spun in “Eight Views of Ornamental Avenue,” wherein Kuti

… takes

a few stabs in that

Sun Ra meets Sly Stone

Fender Rhodes mode

that defers and defers

with blithe complexity

all in the matter

of delaying

the reason we put the record

on in the first place,

that moment when the horns

come in and everything goes

BIG and WIDE

That moment — the paradoxical moment of simultaneous perceptual dilation and pinpoint concentration, along with the resultant rush — is at the heart of Hammertown. Such moments come with a price, of course: after a split second of ecstasy, textual, musical or otherwise, one returns to the rest of one’s life to confront, with heightened sensitivity, the banality and horror of the world-too-much-with-us. On this count, Culley doesn’t flinch and, in fact, Hammertown’s moments of brilliant release are bounded by an acute awareness of the fact that too often we humans seem hell-bent on boring ourselves to death outside big-box stores and up and down strip malls. The book’s opener, “Greetings from Hammertown,” lands the reader squarely in the midst of a far different, if equally overpowering, scene from that of the audiophile’s joy at finding the perfect groove, one in which Culley’s native Vancouver Island’s pre-post-industrial beauty falls incrementally to post-“progress” progress:

Huge uproar lords it wide.

A tim’rous grader halts

before an overflowing ditch, its

big bad boy body slumped

as if thwarted in its gigging …

What follows is worthy of Dante’s Inferno, as “Greetings” leaves us, finally, within “the obscure forest” where

… came the vision

I had sought

through grief and shame –

a caravan

of bright yellow trucks

jostling like bland-mugged thugs

along a granulate roadway

of broken bottles, bristling

with crab claws, with arms like

monstrous barbed

dog cocks, depositing

layer after layer of

sulphurous spoor

into a vale of rubber smokeSleep frightened flies,

and round the rocking dome

howls the savage blast …

The vision of this enduring Dis to the Utopian moments that blip into being through art, music and poetry permeates, but does not dominate. In fact, Culley often seems as likely to glimpse paradise in the “savage blast” as in the “streams of my late youth / cleared and flattened for you / even as I write this.” However, it is art, poetry and music that usually come to the rescue, whether it’s the voice of Kathy Sledge, King Tubby’s dub, the rhythm & rhyme of the poet’s “disease skeltonic” or the poetry and friendship of contemporaries like Kevin Davies and Lee Ann Brown. Culley repeatedly finds his way out of the dejection facing those who would see the world for what it seems to be, often by returning to what it is: a place where any quick value judgment is best suspended, as he warns in an early, aggressive aside:

If you want to read

“decay”

into this rocky heap

of nasty moss, this

eggy newspaper intrusion, that’s your

quattrocento prerogtivo.

Hammertown is just as likely to locate its moment in “decay” as in any well-wrought yearn: The book is virtually dedicated to Philip Guston, whose words provide one of its two epigraphs, the other coming from Olympian Oulipean George Perec’s Life A User’s Manual, which novel provides the literary-nostalgic analog to Nanaimo as an idyllic “fishing port on Vancouver Island, a place called Hammertown, all white with snow, with a few low houses and some fishermen in fur-lined jackets hauling a long, pale hull along the shore.” And as for Guston, his later studies in self-decay appear to key the book’s predominant color scheme of pinks and “rosy grays” and the continual discovery of “…grotesquerie / affirming / the shapeliness of all things….” In the quasi-romantic audiophile ode “Paris 1919” (dedicated to Kurt Cobain via John Cale, Young Werther, Parsifal, Bo Diddley and Sam Phillips, among others — “a mix without edge or limit”) Culley breaks down the case of “decay” thusly:

I’d walk six miles

out of my way

To hear again

the slow decay

Of that piano,

far away—

King Tubby’s

Studio A.

And I’d walk further than that to stay on Peter Culley’s trail, one which stretches — like the epistolary poem “A Letter from Hammertown to East Vancouver and the East Village” — incredibly far and wide and into nooks and crannies long overlooked by the average bear, but nevertheless remains a trail that

… is no secret, either.

a deer trail,

then a dog trail,

then Pete’s trail,

then my trail. Sherpa Tenzing sits puffing

on the roof of the world –

his belief in process absorbed

by the throbbing worm

that mutters and sweats

at the mucky heart

of being …

If you haven’t taken vacation from your senses (but would like to), you simply must visit beautiful, terrible Hammertown. Go now.