As much of a pleasure as it was to appear at the Shanghai International Literary Festival with Jen Bervin, Jen Hyde and Wen Jin, it was one mixed — as is always the case for me here in Shanghai — with significant measures of the odd and the off.

Don’t get me wrong: One of the things I like about life in Shanghai is that the “odd and the off” are clearer in the mix than might otherwise be (or at least this is how it seemed to me prior to the Trumpening, one effect of which has been that many dissonant tones and out-of-sync beats that the producers of the Washington Consensus mix of the late-2oth century hit “Pax Americana” had studio-polished to the point of inaudibility for the ears of smooth-sounds-loving progressives are now gratingly, harshly present in the cacophonous “Make America Great Again” alt right-produced nü metal-new country-no soul-“Trumpism is the new punk rock” undercut hate hit dominating the charts of late).

One place, of course, to detect the odd and the off, is within various neighborhoods of the regime of censorship — the softer the censorship, the better. The hard stuff tells you what you already know. The soft stuff can remind you of what you’d already forgotten — including the fact that yes, discretion is often the better part of valor.

Among the Anglophone expat community in Shanghai, the softest form of censorship is certainly that of the self- variety. The current example, which I go into below: I submitted copy on our Poetry Panel to the SILF, and it was not just altered editorially but critically, and with the Public Security Bureau in mind.

The SILF organizers are fantastic people. They work hard to make an amazing series of events possible, events at which almost anything and nearly everything are discussed with candor, openness and degrees of freedom that would likely shock the many Americans whose ideas about China often seem frozen in some fuzzy Cold War-Cultural Revolution matrix.

At present you can talk about Tiananmen and Tibet, Mao’s vast bad side (all bad? Discuss…) and Xi’s dye-job freely and openly — within expat-saturated Anglophone zones and bubbles (SILF being one, my employer certainly another, the Shanghai Foreign Correspondents Club yet another, and so on).

But you can’t — or you feel you shouldn’t — be too open about it, and you must be ready to defer to the actual censor (if you publish anything for distribution within the PRC) or the censor in your head (if you have, as you do, relationships with PRC citizens, in particular Party members or those who the Party is or may be watching with particular intent).

And state surveillance and censorship dovetails in interesting ways with what other expats want to hear. They’re generally — we are generally — business people. That’s what’s tolerated, more or less: Come for business, do your business, and don’t interfere with anything that’s not your business, such as the policies and practices of the PRC, both internal and external. Have your events and talks and talk about what you like (a good model for keeping an eye on the outsiders, for sure, letting us tend our little gardens of 100 blooming flowers) but keep it to yourselves and watch your words if they might leave the Special Zone (I work in a very special zone).

This all worked in a couple of ways when it came to the poetry events I organized and participated in at SILF. In the grand scheme, exceedingly minor, yet, even as minor symptoms, quite telling with respect to the grand scheme.

The first: My submitted promotional copy for our event went from describing my work as reflecting on “the experience of expatriation in a time of growing planetary crisis, even as China and its expat population are celebrated (and often celebrate themselves) as engines of progressive globalization” to reflecting on “the experience of of expatriation in a period of progressive globalisation.”

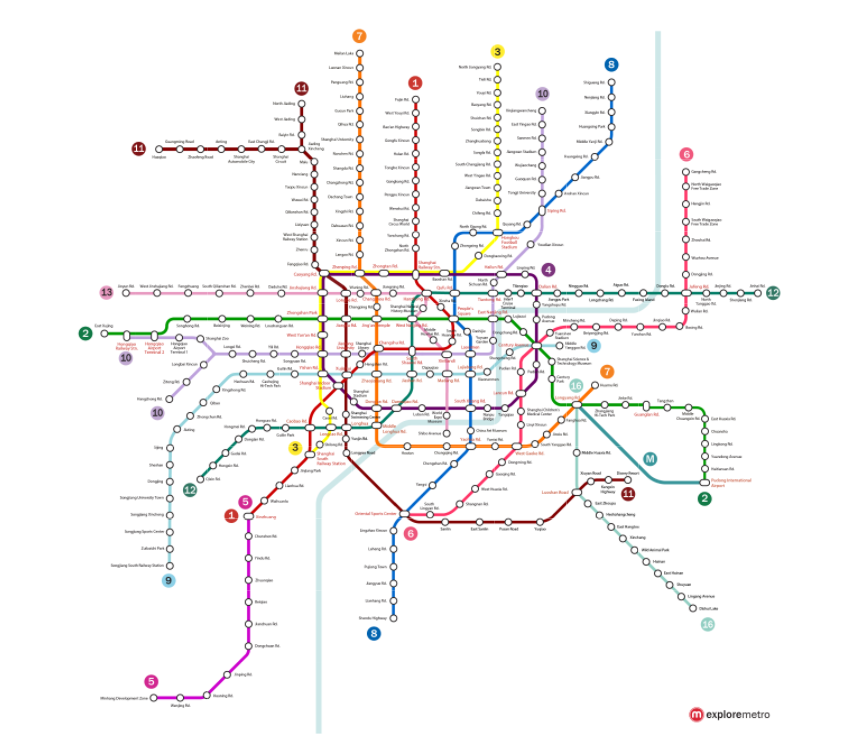

The organizers are careful readers and good editors, so I didn’t think, when I saw the printed brochure (see the scanned image below) that this was just an editing error. My suspicion was confirmed when I pointed out that the brochure copy was a long way from my intended meaning, in fact, it was nearly opposite. The email response: “…we were simply trying to avoid any controversy on the printed program since the PSB does check up on us.”

Printed matter is a real sticky point to be sure, and I understood. Digital content is different, and the organizers changed the Web copy to “the experience of expatriation in a time of globalisation in deepening crisis.”

Good enough, and I’m glad to have the print brochure souvenir, even as it grates. It’s the the off and the odd, after all, and I like it like I like a look of agony (or at least awkwardness or embarrassment), because I know it’s (more likely to be) true: yes, we are and I am party to censorship, and we do it ourselves.

(Continued)