Chernobyl with youth group.

Now in light of Fukushima, we are afraid.

“Museum of Oblivion” review.

Mixed material dioramas by Tatu Tuominen and Tuoman Laitinen; HD video and light box video stills and photographs by Tuomas Laitinen; acrylic, cut paper and epoxy on aluminum-composite works by Tatu Tuominen at Art Plus Shanghai, Shanghai. Jan 8 – Mar 6 2011.

There’s a certain post-industrial, surrealist noir whodunit vibe to the Museum of Oblivion that is as familiar as it is discomfiting, if only because, amidst the atmospherics, there’s really no mystery at all: You dunit. And so did I. All of us have, actually, and we’re still doing it — this much is as certain as oblivion.

And no, it’s not that we’re “killing the planet” nor even that we’re just “ruining the planet.” Such claims are far too grandiose and simplistic. We’re merely changing the planet, irrevocably, and it’s frightening, confusing and, yet, at times oddly fun—if, ultimately, only in the ironic sense of “fun” also on display at the recent Moon Life Concept Store in Shanghai. And as the latter sought to play with the notion of commoditizing an end-of-the-world-as-we-know-it future, with “Museum of Oblivion,” Tatu Tuominen and Tuoman Laitinen, two Finnish artists, play with the notion of curating this selfsame future, presenting both individual works alongside a set of collaborative dioramas.

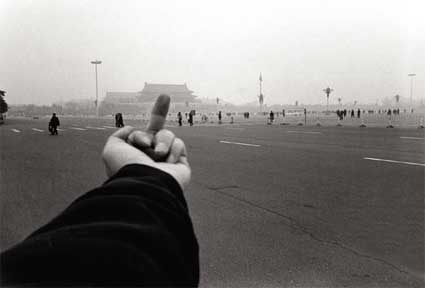

The dioramas depict four sites of manmade disasters of a scale previously associated only with natural ones — the New Orleans flood (made possible by poorly engineered levees), the toxic desert-dry exposed bed of the vanishing Aral Sea (massive Soviet-era diversions of waters to irrigate cotton grown in arid regions), a pair of Chernobyl apartment towers (nuclear reactor meltdown), and a patch of generic desert that is surely somewhere in particular (if not now, then in the future) but could be any number of places with its yellow sand and ruined three-story brick building.

Populating these scenes, however, are a slew of leisure-seeking humans: a pair of sunbathers loll on a beach blanket in the desert; an all-terrain race car kicks up dust between the hulking forms of ships stranded by receding Aral Sea waters; folks waterskiing down a flooded New Orleans street; and a class of grade school kids are led on a field trip through Chernobyl. Trenchant, mordant and wry — and all the more effective for not taking itself too seriously — the work implicates the viewer both as participant in and spectator of the catastrophic changes underway all around us, as well as the consumerist spectacles that divert our attention and keep us relatively oblivious.

Accompanying the dioramas are bodies of work by each individual artist: Tuomas Laitinen’s surrealistic HD video “Rising” (2010) and an accompanying set of light box stills; and scenes by Tatu Tuominen constructed of layered clear epoxy giving plastic depth to intricate paper cutout forms.

Projected upon a slightly curved suspended slab of what appears to be aluminum, “Rising” refreshes one of our oldest collective narratives — the archetypal descent into the underworld. In this case, the underworld is an abandoned factory into which wanders a pubescent girl. She passes through spaces also occupied by a puttering elderly caretaker, a pair of white-jumpsuit-and-black-bowler-sporting figures that bring Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange to mind, and a shadowy Death figure worthy of a Seventh Seal remake. Amidst shots of a factory control room, a dusty cathedral-like space and dark stairways, and occasional showers of flying sparks, a quasi-Lynchian surrealism emerges at points, as in a scene in which the two pseudo-Droogs act as post-consumer-waste undertakers, burying a sparking, smoking empty microwave in a shallow pit. One figure, the man, had arrived on cross-country skis; the other, a woman, had come hauling a mini-shopping cart full of junk (including the doomed microwave) by rope. In the end, a massive smokestack provides another inventive reimagining of a traditional trope for passage from life to death: light at the end of the tunnel. Shot from within the smokestack looking up, ascending sparks and smoke come to obscure the light by the end of the video, leaving the viewer in a state of post-dream/reverie disquiet and ambivalence. All in all, “Rising” can be taken, among other things, as a darker — and quirkier — meditation on the notions of ruin and oblivion touched more lightly upon by the dioramas.

Tatu Tuominen’s paper cutouts present us with additional seemingly haunted scenes, from forests in silhouette against deep red skies to drably functional apartment blocks to ranks of vinyl LPs rendered in a ghastly radioactive yellow-green. Tuominen’s images, built up between layers of epoxy and tinted in acid acrylic and enamel hues, focus our attention on spaces marked and structured by human activity, but with an air of menace, as if our cities and vintage record shops might give rise at any second to cinematic eruptions of violence. “Park Bench People 2,” for instance, gives us a traditional church with its steeple and surrounding gardens in the acid pinks and oranges of an emulsified old film negative — a look familiar from horror movies, perhaps, or a water-damaged photo turned up at a flea market. And though viewers would be forgiven for seeing the heavy influence of David Thorpe’s paper collages from the late 1990s, Tuominen’s high-gloss epoxy surfaces succeed in the context of the full show as elements in a conversation about “oblivion” as a manufactured and presently inhabited imaginary space on one hand, and the terminal point of our developmental trajectory on the other.

In the end, the show succeeds because it takes itself neither too seriously nor too lightly. It’s easy enough, perhaps, to feel upon cursory consideration that the individual elements gathered here have been tossed into a convenient — and portentous — conceptual basket, but given a little time and taken as a whole (be sure to take in all seventeen minutes or so of “Rising”) Tuominen and Laitinen’s work manages a sidelong glimpse of something like our age’s “sublime,” a sublime in a time of climate change, one rooted in hulking industrial wrecks and manmade disaster sites rather than the mountains, skies and seascapes of more romantic days.

On, yes, blackjackchamp.com. Of course.

On, yes, blackjackchamp.com. Of course.